The evolution of software might be a story of innovation in delivery channels – the mainframe to the personal computer, hardware-specific applications to cross-architecture compilation, desktop to mobile, on-premise to cloud. These new delivery methods represented a unique opportunity for developers to reach more users with the same application. The benefits are obvious: write once, make available anywhere. We might use the word portability, then, in very general terms, as a characteristic of software: highly portable software can be written once and deployed anywhere.

Portable applications require less development and operational effort even as they are exposed to more potential users. This same value, though, also applies to the internal operations of software teams. In modern microservice architectures, developers also play the role of consumers- consuming the services and APIs created by other teams both inside and outside of their organization. Thus, application portability matters significantly to the internal operations of software companies.

Today, we’ll shed light on what portability means in the context of cloud software and why it’s important for both your customers and your team members.

“It works on my machine”

Software teams generally use the word “environment” to describe the context in which an application runs. It’s a broad term- you might use it to refer to a specific machine, an OS, or an entire network. Importantly, the word captures a fundamental concept with a serious implication: context differs across environments, and if your software depends on context, its behavior will differ across environments! This distinction is often the culprit of poorly functioning software: it seemingly works in one place but is buggy when you run it somewhere else.

Picking apart the logic of your software from the characteristics of the environment is a central skill in developing any software application, and it’s a skill that strives toward the above prize: portability. A developer who has isolated their software from its environment finds themselves with an elegant bundle of business logic that will behave the same regardless of where it is run: their own machine, the company QA environment, their production cloud, even their customer’s cloud!

Who benefits from software portability?

IT departments: commoditizing cloud providers

A smart business will limit its hard dependencies if given the chance. Vendor lock-in introduces a central point of failure that exposes a company both to disruptions in service and the pricing whims of the vendor. Horizontal application portability is characterized by minimizing environment switching costs such that an IT department can avoid vendor lock-in. If you can run your application just as easily on GCP or AWS you avoid pinning your company to the uptime and pricing of one cloud provider.

Developers and DevOps: building and releasing extensible services

It is not uncommon for environments to multiply rapidly in even small software teams. Developers need to run the application locally, quality engineers in a test environment, sales reps in a demo environment, and operators run the application in staging and production.

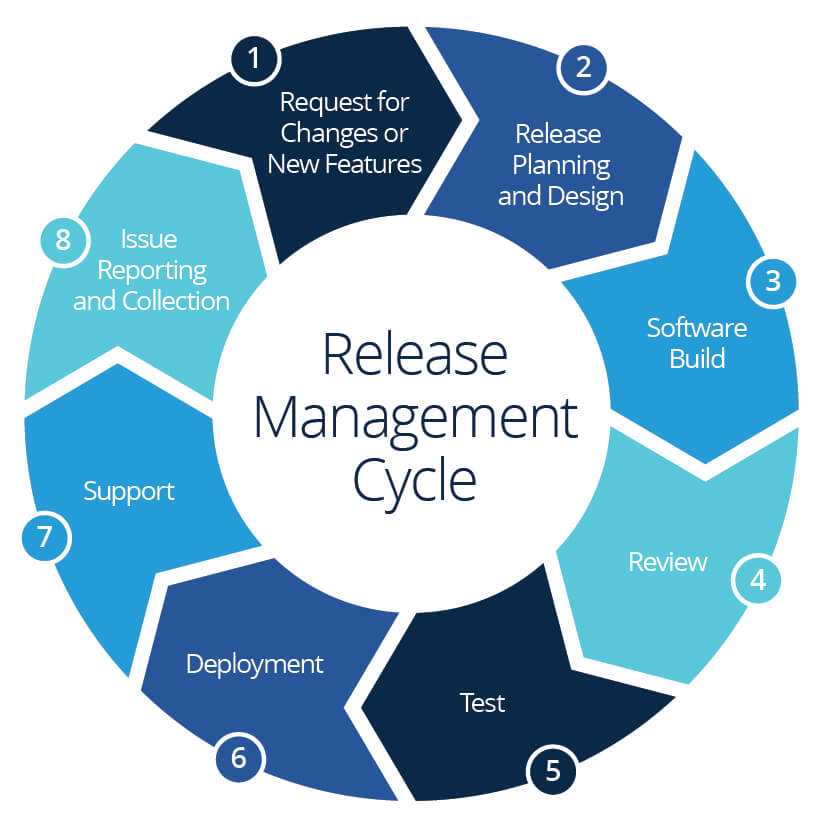

The develop/test/demo/deploy lifecycle has a cost that is directly correlated to the portability of the application. Software that requires much environment-related configuration and tuning will cost time and effort as new versions move through the lifecycle. Portability saves time and mental overhead for anyone involved in moving new versions of the software across environments.

Sales: increasing addressable market

Many potential customers prefer to run vendor software on their own premises for security reasons. If a business makes rigid software – requiring specific operating systems, cloud providers, embedded security, and extensive environment configuration – the business is inadvertently limiting its addressable market to those customers that satisfy these conditions. A company that ships portable software, on the other hand, removes these restrictions on their addressable market.

The three dimensions of software portability

Building software that is portable actually encourages patterns that support a host of other worthwhile properties. Suppose you make it easier for your software to be run here or there. It follows that it is easier to run it here and there: supporting replication within and across environments and enabling engineers across teams and orgs to operate the software themselves. An application that provides full portability and is easy for developers to run is easier to build on top of. An application with great portability lends itself to great extensibility.

So how do we know if our apps and services are portable? Can they be portable in some ways and not others? To determine this for ourselves, let’s evaluate three different dimensions in which our application can be portable:

1. Replication (deep)

The first dimension of portability is crucial to operating cloud applications at scale – scaling and replication. The ability for your service to maintain multiple running instances that work as a cohesive unit is paramount to its ability to support concurrent users at scale. Consistent packaging mechanics, like VM images and containers, are often the key to automating the replication of services in cloud environments at scale. Still, this replication demands consistent methods for load balancing and distributing incoming traffic. By combining packaging consistency with API gateways, service meshes, and other load balancing solutions, teams can quickly achieve deep application portability.

2. Platform/provider migration (horizontal)

The second dimension of portability is typically the first that most think of when they consider cloud portability – cloud migration and/or multi-cloud deployments. The ability for your application to be run on multiple platforms is a great defensive strategy. It ensures that cloud apps can remain cost-effective and protected from outages. Designing applications to be run on commodity infrastructure (e.g., Linux vs. Windows) or on multiple cloud providers (e.g., AWS vs. Azure vs. GCP) enables teams to run in multiple locations concurrently or swap out providers should pricing prove beneficial.

3. Development lifecycle (vertical)

The third dimension of portability is often overlooked despite being far more impactful than horizontal mobility. This is portability through the software development release cycle. Software developers are constantly building or modifying services inside an application stack. As such, they find themselves needing to test in environments that they can be sure will match production. The consistency of the application context from local development, through test/QA/staging, and finally to production environments is crucial to ensuring trust, maintaining a strong development flow, and ensuring that product features get in front of customers quickly and safely.

History and future

The yearning for portable software is not new. The development of the Java Virtual Machine is among the most successful software portability innovations to date. Now, any machine can run a single compiled .jar file and any OS and display identical behavior. With Docker, applications can go a step further: an entire OS can be shipped as a lightweight artifact and run anywhere.

Note the caveats, and note the seeming inconsistencies with the entire concept of portability! If java needs a JVM installed, isn’t that a hard violation of everything we’ve discussed? Alas, it seems so. Here lies another, related- even inverse- concept to portability: the platform. Portable software still needs be executed by something; a platform, an OS, an environment. As developers struggle to make their applications more portable, companies struggle to make the “universal platform” on which all applications might be run portable. Microsoft tried it with an OS, Oracle with a narrow VM, Docker with a more general VM, and most recently Kubernetes with an open-source hardware abstraction and Terraform/Cloudformation with reproducible infrastructure-as-code templates.

True portability

Are applications truly portable? The best way to answer that is to look at our own applications. Are my applications portable? Can I share my application with other developers? Can they run or access it using their own tools and hardware?

The industry has made enormous strides toward allowing cloud software to become portable. With each innovation comes a new opportunity for software architecture to push the boundaries even further. Yesterday I could make a portable monolithic application by putting it in an AMI or Docker image. Today my app contains multiple images that run separately yet still need to connect together. The pursuit of portability is an ever ongoing effort, but the value of the pursuit always remains.

Add your thoughts